ONEIRIC.SPACE

Interview 006, Psychology, Philosophy, Spirituality

Misa Tsuruta examines how culture shapes

our relationship to dreams

Interview by Charmaine Li

ONEIRIC.SPACE

Interview 006, Psychology, Philosophy, Spirituality

Misa Tsuruta examines how culture shapes

our relationship to dreams

INTERVIEW BY CHARMAINE LI

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANA SANTL

INTERVIEW BY CHARMAINE LI

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANA SANTL

Everyone dreams—but how dreams are seen, shared and understood varies from culture to culture. Some cultures treat dreams as social entities that can be incubated within a community, others consider them to be psychological phenomena that stem from the inner self. Tokyo-based psychotherapist Misa Tsuruta examines how culture shapes the way we think about dreams and the waking narratives we create about them through her research and writing. We spoke to her about the dream journals of a well-known Japanese Buddhist monk from the twelfth century, the role of dreams in modern Japan and the cultural differences and similarities in dreams and personal narratives between American and Japanese students.

CHARMAINE LI: My understanding is that you completed a bachelor’s degree in law and worked in the corporate world for a few years before going on to pursue graduate studies in psychology in New York. Why did you decide to eventually focus on psychology and, later on, dream studies?

MISA TSURUTA: I would have preferred not to go into law, but that’s what my father recommended to me at the time. In the end, I did apply to study law and felt very conflicted about the decision, both in college and even afterward. It took me a while to start my career in psychology and it wasn’t until my mid-twenties, when I moved to New York City, that I started studying it. I was also doing personal psychoanalytic therapy, which got me interested in dreams.

“ I was fascinated by the process of looking within myself, having a deeper dialogue with my inner world and by what I discovered from this kind of introspection. ”

Did you remember your dreams as a child or have a relationship with your dream world growing up?

I don’t particularly recall remembering my dreams much as a child. I think it’s when I started to become interested in psychology and psychotherapy that my dreams became richer. And then I started to tell people about them, kept dream journals and joined organizations such as the International Association for the Study of Dreams (IASD).

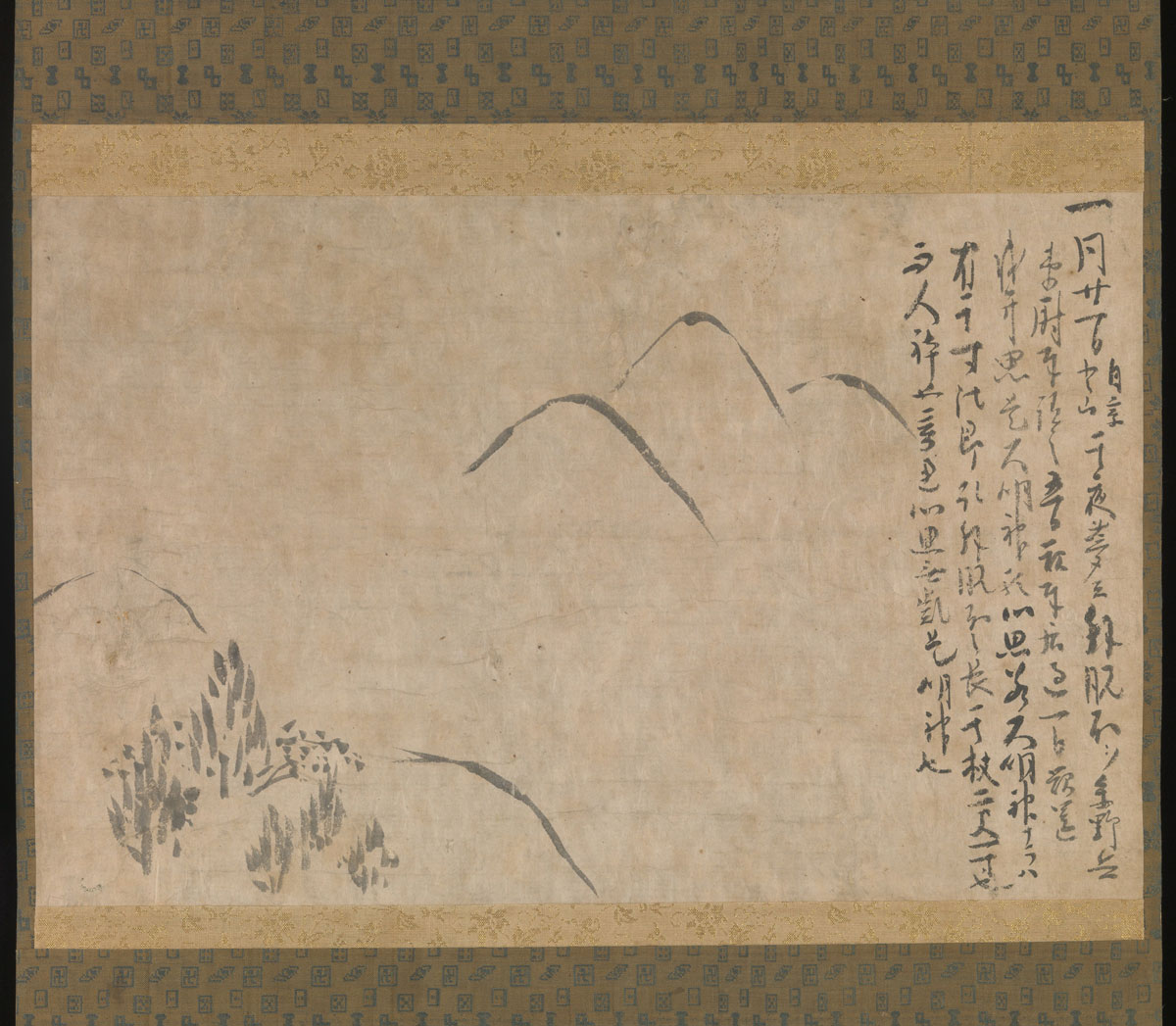

Section of the Dream Diary (Yume no ki) with a Sketch of Mountains by Myōe Kōben. ca 1203-10. Hanging scroll; ink on paper.

I wanted to ask you about one of the prominent dreamers in Japanese history named Myōe (1173-1232) that you’ve spoken about at the IASD conference. Could you introduce us to him?

Myōe was a Buddhist priest who lived in the twelfth century during the transition from the Heian period to the Kamakura period. During this time in Japanese society, the power shifted from the aristocrats to the warriors—so the samurais. As a child, Myōe lost his parents and was then sent to live in a temple. He wanted to be a Buddhist monk early on and went on to study the Kegon sect of Buddhism, which he wanted to rejuvenate and preserve. He was very critical of his Buddhist peers at the time and was so devoted to his practice that in one instance he cut off his ear to prove it. Later on, Myōe founded and led the Kōzan-ji Temple in the mountains of Toganoo, near Kyoto. He’s very well-known for keeping dream journals from the age of 19 to 58—and they still exist today. They’re actually kept in a few different places around Kyoto. It’s quite amazing that we still have access to these dreams records from the twelfth century.

What kind of role did dreams play in Myōe’s life?

Myōe was a deeply spiritual person who also had visions in waking life as well as in dreams. Twice, he attempted to make a pilgrimage to India because he was incredibly drawn to Buddhism from India. You have to remember, back then it wasn’t easy to travel to India as it is now. You could get sick or even die from undertaking such a trip. Even though he was ready to embark on the trips, what stopped him from going both times was a series of dreams and visions with the message that he shouldn’t go.

My guess is that because he studied the Kegon School of Buddhism—which is difficult for me to explain even though I’ve read a few books about it—this made him more open to looking into all aspects of the lived experience as well as all kinds of beings. And my understanding is that because dreams are phenomenologically part of our experiences, he also took an interest in them.

I read somewhere that you’ve been keeping a dream journal for more than ten years. Can you tell us more about what motivated you to start a dream journal in the first place?

I started my dream journals in the early 2000s, so it’s now been more than ten years but less than twenty years. In the beginning, I was keeping “normal” journals where I wrote about waking life and reflected on thoughts. When I had a dream, I also incorporated that into my journal. Eventually, I stopped recording my waking experiences altogether and was somehow left with a journal with only my dreams in it. Sometimes I would include significant experiences prior to the dream to make the connection between a dream and waking events though. Now, I have a box of notebooks and I don’t know what to do with them. Some people have suggested that I transcribe them and create a system so I can search certain words, themes, or topics, but I haven’t done it yet. It’s such an overwhelming task.

Do you ever go back to your dream journals and look through them?

I do, but it's quite demanding and time-consuming. So I usually only do this when a dream conference is approaching or when I have some extra time to look into something that I need.

“ It’s very interesting though because it’s like getting a snapshot of your mental life at a certain point in time. ”

You wrote an interesting article introducing dream practices and dream-related arts in ancient, medieval and modern Japan that was published more than a decade ago. I’m curious to hear more about the importance of dreams in Japanese culture and society today…

I think people talk about their dreams casually among their friends or colleagues but very rarely do they talk to professionals about them to explore them more deeply. I think one difference in the way that Western cultures approach dreams compared to the Japanese culture is that they’re more interpretation-oriented—they like to explore and analyze them. Whereas in Japanese culture, it seems like the approach towards looking at a dream is a bit shallow. It feels to me a bit more impressionistic. In Japan, I would even say that psychologists and psychotherapists are sometimes seen at the same level as fortune-tellers. As an academically trained therapist, I often feel frustrated by how some people don’t make the distinction between fortune-tellers and psychotherapists. That might also be because a lot of people are afraid of looking within themselves and it’s often easier to seek external advice that “promises” successful outcomes.

Your doctoral dissertation, published in 2016, explored the cultural differences and similarities in dreams and personal narratives between American and Japanese undergraduate and graduate students. What are some of the most interesting things you learned while conducting your research?

In terms of the findings, one was that Americans had a tendency to believe that dreams derived from internal and psychological sources, while the idea that dreams came from external sources—such as being sent from gods, spirits or supernatural powers—was more popular in non-Western cultures. When compared to the Japanese in particular, Americans believed more strongly that dreams come from internal sources, but this doesn’t mean that the Japanese believed in external sources.

Another thing that was interesting was that Americans mentioned negative emotions more often in their personal narratives than the Japanese did. The total number of positive and negative emotions mentioned by Americans in their personal narratives was also higher than those of Japanese. That wasn’t very surprising to me because, from my experience, when Japanese people mention negative emotions to others, they often worry that it might become a burden to others. It’s also common in psychotherapy where the patient might not want to disclose negative emotions because they fear the therapist will be burdened or bothered by it.

As someone who was born in Japan and then went on to study in the US for many years, I’m curious to hear about how you see yourself in relation to the spectrum of your findings?

It’s difficult to answer. Even though I have a psychotherapy practice in Tokyo, I often feel like my professional life is very much tied with the training I received in the US. Even though I’m more fluent in Japanese than in English, there are certain psychological expressions that I feel much more comfortable discussing in English because I used them so frequently during my time in the US and now for work.

Actually, I’ve been working with a colleague from IASD to try to spark more interest in dreams in Japan, but he’s been kind of slow in moving things forward. It seems to me that perhaps—again like I mentioned earlier—it’s related to how there’s only a passing interest in dreams in Japan and many people don’t think it deserves deeper exploration. Also, it seems many people are too busy working long hours and not sleeping enough in Japan to recall dreams and work on them! I would say it’s not a very healthy lifestyle. In this regard, I guess I’d say I lean on the American outlook towards dreams.

How do you see culture shaping dream life?

That’s a big question. I think culture affects the way people think, feel and behave—their psychology, in general. So growing up in a particular household, family, school or neighborhood shapes how you think, feel and behave as well as who you are. I believe dreams are no exception to the effects of culture since they reflect our waking lives in some way. And I think that’s the reason I wanted to pursue cross-cultural research on the topic.

But nowadays, things are much more complex with increased mobility. For example, you’re a Canadian living in Berlin. And I was born in Japan, grew up there, studied in New York and then came to Japan to work as a psychotherapist in both Japanese and English. With globalization, it’s difficult to concretely define what Japanese or American culture means today, which of course makes things more difficult for conducting research on the topic.

“ I believe dreams are no exception to the effects of culture since they reflect our waking lives in some way. ”

THE INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED AND CONDENSED.

Want a monthly digest of articles, resources and quotes exploring our relationship to dreams delivered straight to your inbox?

Subscribe